shame, regret, cynicism

The face she shows me is a little sour,

Though sugar has never tasted sweeter.

Sugar would be bored by its own sweetness

If it ever came to know that sour flavor.

#1795: From Rumi's Kolliyaat-e Shams-e Tabrizi

I woke with a bitter taste in my mouth. I felt shame, regret and cynicism. None of these words yielded a first line but I noticed the sour in the line at the top of the index and also the she. This was it, then. My own face, surely, was showing itself "a little sour".

We currently live in an age of cynicism, a so-called "post-modern" time where everything is "deconstructed". The heroic and the hopeful have suffered a good deal of bad press as a consequence. There is certainly a sticky sentimentality that can adhere to our images of love especially.

I wonder at Rumi's use of she here. This verse is just one among many that celebrate his love for Shams. He rarely directly laments the subsequent loss, the absence of his beloved. There is a joy of love that transcends both the ordinary joy and the bitterness of love. That transcendent joy is not sentimental like the first for it acknowledges and even honours sadness, sourness, the day-to-day realities of love.

I've been reading Erich Fromm's Greatness and Limitations of Freud's Thought and Rumi came up in this paragraph:

It is most important to note that Freud and his disciples usually speak of "object love" (in contrast to "narcissistic love") and of a "love-object" (meaning the person one loves). Is there really such a thing as a "love-object"? Does not the loved person cease to be an object, i.e., something outside and opposed to me (same root as in to object)? To speak of love-objects is to speak of having, with exclusion of any form of being; it is not different from a merchant speaking of capital investment. In the latter case capital is invested, in the former, libido. It is only logical that frequently in psychoanalytic literature one speaks of love as libidinous "investment" in an object. It takes the banality of a business culture to reduce the love of God, of men and women, of mankind to an investment; or the enthusiasm of a Rumi, Eckhart, Shakespeare, Schweitzer to show the smallness of the imagination of people whose class considers investment and profit to be the very meaning of life.

So love has a bad name: on the one hand an empty sentimentality and on the other a cynical exploitation. I'm not sure of love myself. I'm not sure I've ever known it, for I doubt I can ever have steered so accurately between the Scylla of sentimentality and Charybdis of cynicism.

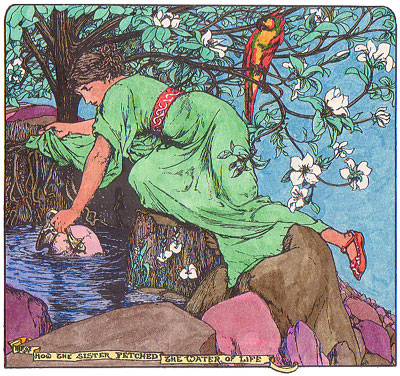

One of my favourite fairy tales is The Water of Life from Andrew Lang's The Pink Fairy Book. In it, a heroine succeeds in rescuing her three brothers from a stoney spell (a result of cynicism or listening to voices of derision). She follows the instruction of a helpful giant to just keep going and not turn towards the mocking voices. She thus stays focussed on her task and reaches the summit of a mountain where lies the water of life (and the talking bird and the tree of beauty).

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home