ephemerides

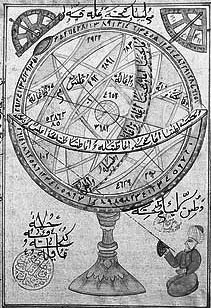

In this illustration from a 16th-century Ottoman manuscript, an astronomer calculates the position of a star with an armillary sphere and a quadrant.

The second difficulty the author confronts is the notion that Abu Hamid al-Ghazali (d. 1111), probably the greatest Muslim religious philosopher, put an end to scientific activity in the Muslim world by his attack on the philosophers. This simplistic formula is also a nineteenth-century view first put forward by Edward Sachau. Here again the reader is given no background on the debate, no clue about what Ghazali argued, how Muslims reacted to the arguments, nor the century-long debate that culminated in a rebuttal by Averroes (Ibn Rushd) in the twelfth century. At issue was Ghazali's denial of natural causality and his marshaling of Greek philosophy to the aid of "Islamic occasionalism," the view that all events, human and natural, are controlled by God instead of through the blind workings of natural processes.

Whatever impact that doctrine had on Muslims, Saliba's exaggerated imputation to Ghazali claims too much. At the same time, he fails to draw an obvious insight that applies to astronomy. The author notes that one objection to Greek astronomy in the Muslim world was its association with astrology, as astrologers claim to predict the future. Such a claim is profoundly at odds with the Islamic view that only God knows the future, encouraging the extreme reluctance of Arab astronomers to work out ephemerides, tables listing the positions of the sun, moon, and planets on a daily, weekly, or monthly basis. Saliba acknowledges the surprising absence of ephemerides but declines to comment on the deeper issues.

from Toby E. Huff's review of George Saliba: Islamic Science and the Making of the European Renaissance.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home